Avionics Technician

Photo courtesy John Hogan

When it comes to flying, every instrument in the cockpit has a critical role—and John Hogan is the one making sure they all work flawlessly. He’s responsible for ensuring that planes are fully equipped and functioning so pilots can focus on doing their jobs safely. We spoke with him about the challenges of keeping complex systems running smoothly and what it’s like to find your niche as an engineer.

Name: John Hogan

Occupation: Avionics Technician

Okay, But What Do You Do?: I make sure that planes are able to do all the things that they can. I make sure that all of the instruments in the plane work properly so that the pilot can do [their] job better.

What is your official job title?

Avionics Technician.

What exactly is avionics?

Avionics is essentially all of the electronics that go into aircraft. It's a mashup of aviation and electronics. Most of it has to deal with the cockpit and the interfaces that the pilots deal with, but it's all throughout the plane on some of the bigger ones.

Can you walk me through your career to date?

Well, I started off in automotive. I went to school for mechanical engineering and went into automotive down in metro Detroit. After that, I transitioned into more electrical stuff because that's what I was interested in. I'm a bit of a computer hobbyist in my home life, so [it] seemed like a natural transition. Got into power transformers, and then after [my wife] and I met, we moved to Traverse City and there's not a ton of that up here. So I had a brief stint in hydraulics before landing in aviation.

There was an old avionics shop [there] that was bought by the parent company that I work for, and they were looking for people with general electrical and mechanical experience to come in and learn. I'd only been in aviation for about three years, but it's been fun. At the end of the day, it all boils down to the same stuff. A wire is a wire, a circuit breaker is a circuit breaker. Whether it's going in a car, a house, or an airplane, it all works the same.

What type of training is needed in general to work in avionics? And what did you do as part of your transition?

Most of what we do where I work has been OJT, which is just On The Job training. I had a supervisor and mentor who'd been in the field for 20-30 years walk me through a lot of this stuff and show me the ropes. I also went to a couple of training classes. A lot of it's online, you can search most of it on YouTube. There are certain webinars out there provided by some of the bigger manufacturers, Garmin being the number one of them for us. We're a Garmin aviation dealer, so we have access to training videos and seminars and in person classes and a whole bunch of stuff through them. I did a lot of that.

Then there was a convention for the Aircraft Electronics Association that I went to a couple years ago. They provide a whole slew of classes ranging from physical hands-on installation to transponder theory and a whole bunch of other stuff in between. That was a big one for me, it really taught me the ins and outs of, you know, “How does this screen talk to this screen? How do these components talk to the ones in the back? How does it all mesh?” It was a lot of fun and I enjoyed it. It was going on for a week–I think we attended for four days. They had all the classes on the middle three days, and then on the last day, they had an exam and a certification class, and you could get your license there. I have the aircraft electronics technician certification, so it says NCATT. That's my cert[ification] that I got from them.

Through working at a certified repair station, you can become a repairman, and that is when the FAA certifies that you, as a technician, are certified to install certain avionics and equipment into the planes. Can't just be anybody off the street, and to get that, you have to have two years of work experience and then one of these certifications.

Avionics wire harness connections | Photo courtesy John Hogan

What types of planes or aircrafts do you work with most often?

The company I work for is also a charter company. We have our own fleet of aircrafts that we charter out to people who want to fly over to Milwaukee for a weekend or go golfing down south somewhere for a week or something. So we do work on a lot of bigger stuff, King Air business jets, that kind of thing. But that's mostly for small problems. The bulk of our work comes through what's known as a “general aviation aircraft.” And that's your dad or uncle or aunt or somebody got into flying, got their license and wanted to buy a plane. So they buy, like, a Cessna 172 or a Piper Arrow or something, and it's usually a little two seater or four seater aircraft, very lightweight.

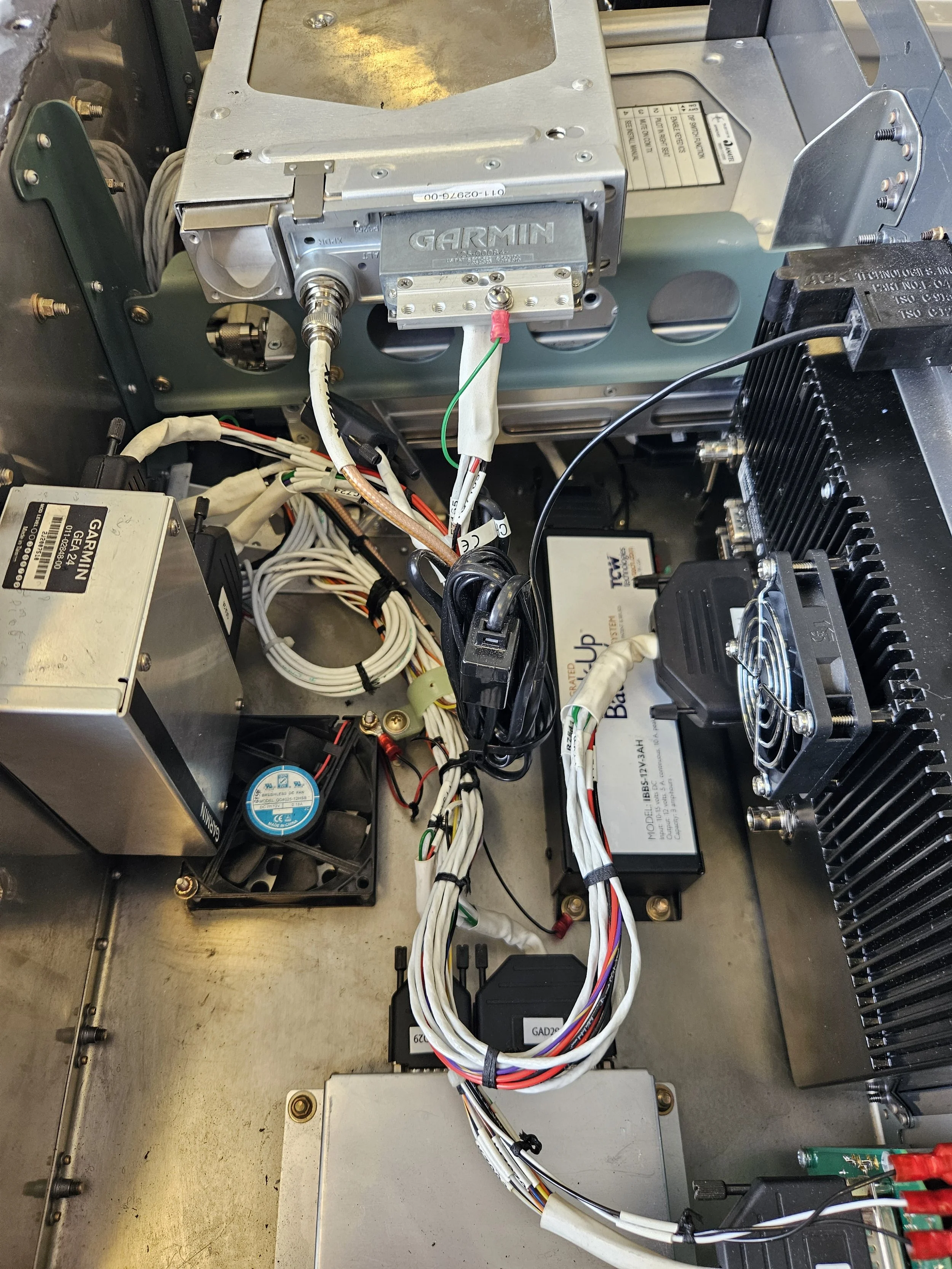

A lot of these planes are older, from the ‘70s or ‘80s even, and they're running on vacuum and steam gauges. What they'll have us do is gut the cockpit, the instrument panel, and put in newer stuff so you get touchscreen panels and digital avionics. A lot of that is where having the tactical expertise comes in, because you can't just plug [in] and it all works. Depending on what instruments you have, [the equipment] talks on a different channel or it talks at a different speed than the others. So it's a lot of reading, really, what it boils down to. Reading all the manuals.

Upgrading a jet cockpit | Photo courtesy John Hogan

Do you need to use different processes on the different planes you work on?

Oh, yes. Say you have a Cessna 172 that's getting a certain upgrade to it. It's going to be different than [your] friend's Cessna 172 that's getting the same upgrade, because it depends on what else they have in their plane. If they have a certain navigator, [it] might talk differently than a different kind of navigator. There are different manufacturers out there that make the same things, essentially, but it's wired differently and the software interacts differently. Somebody could have a Garmin navigation system and somebody else could have an Aspen navigation system or an Avidyne navigation system. This comes down to reading the manuals [to see] how you need to configure them and wire them to get them all to talk to each other. We run into a lot of that. One of our fleet planes is a hodgepodge of different manufacturers, and it's always a whole lot of fun to figure out what's going on when a plane has a problem.

What are some of the most common challenges you face in this role?

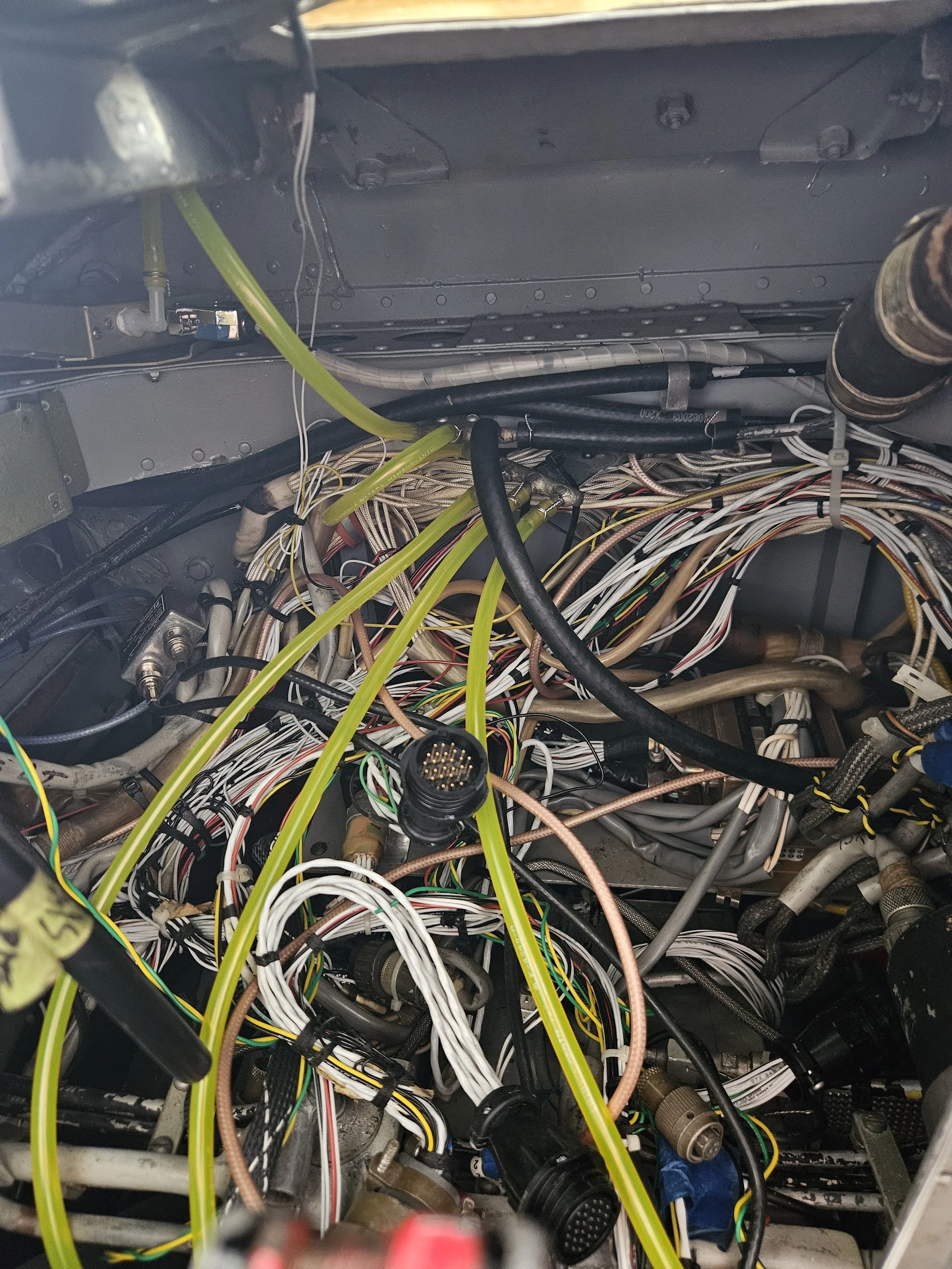

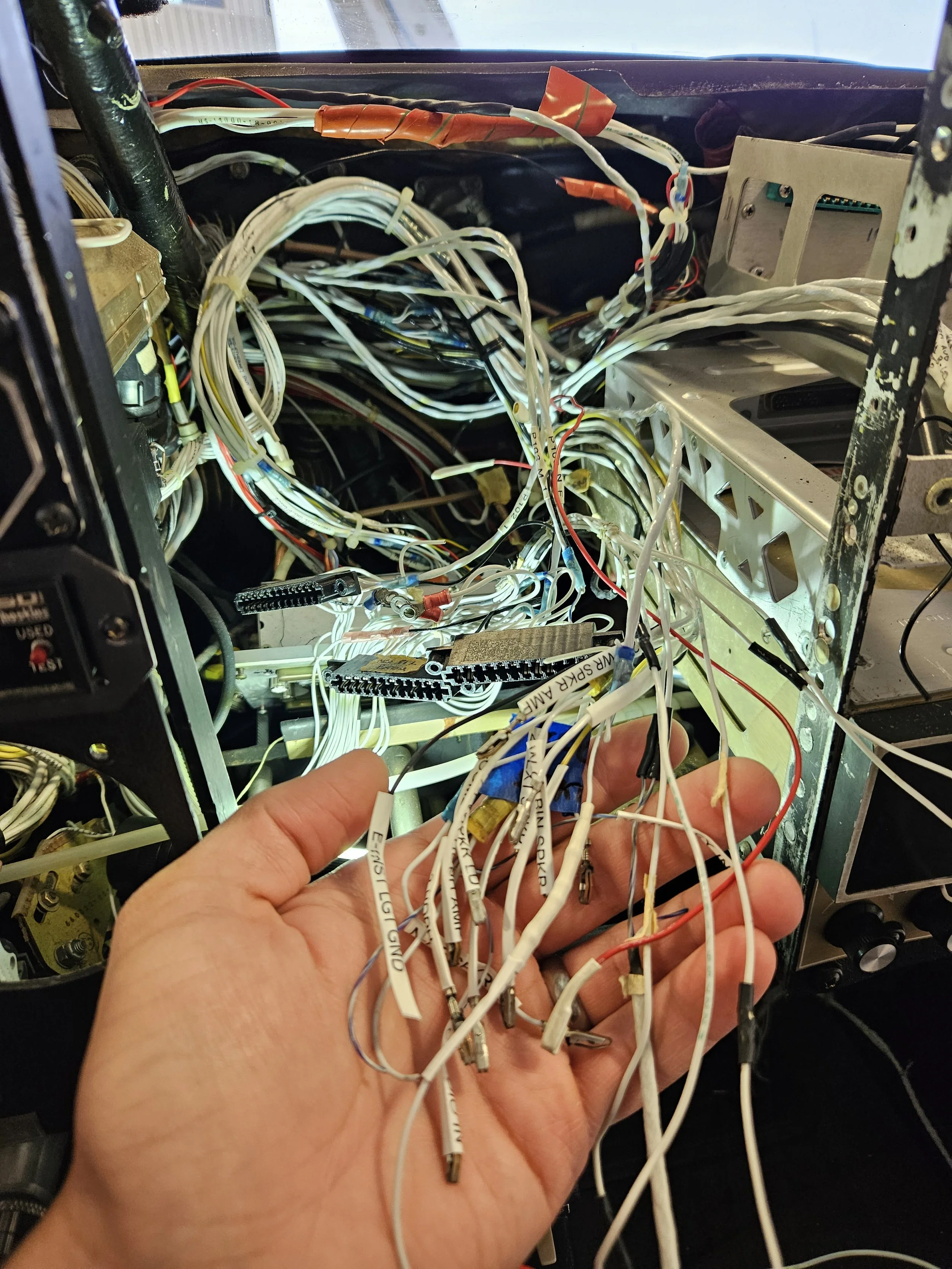

Well, today, for example, I had four projects going on. One being an autopilot installation where it's a newer system, but a lot of the wiring was left in there tangled. We had to gut it and figure out what's actually necessary. People tend to, when they do upgrades, leave all the old stuff in there and it turns into a rat's nest of wires. So it takes a lot of [pulling] the wires out, finding out which ones are being used, which ones aren't, which ones need to come out, which ones need to stay.

“The magic behind an aircraft panel” | Photo courtesy John Hogan

I had one technician working on that. Then one of our flight schools on the airfield here had a problem with one of his planes, and need[ed] us to take a look. One of the screens wasn't talking to the other screen. For that problem, you have to dig into the wiring, make sure that the pins are seated correctly, make sure the connectors are all the way seated, and make sure that the configuration settings are set right. And then make sure that the software is updated all the way, because any one of those things could be causing the issue.

Another project today was, my boss is at a convention and he's talking with some people and they wanted to get a quote for some experimental jet thing. So I had to take their list of requests and start digging into Garmin manuals: they want this and this…does this system actually provide that or do you need that system plus a different system? The number one challenge is making sure everything is going to work together, because when you design these systems, you think it's all going to but for some reason or another it might not. And that's a real problem down the line.

The manuals aren’t referencing those other things, though, right? You're reading all of them and determining just through your own knowledge and experience if it will work?

It comes through experience and having already read all the fine print and the notes of the wiring diagrams that, “If you're trying to connect this to this, make sure you use this instead of the main one, otherwise you'll have a problem. If you're running into this problem, make sure you update the software first before you check anything else, because the old software didn't like it when you did that.”, those kinds of things. But the installation manuals for the Garmin products, especially, are very in-depth and always being updated with new revisions as new products come out. It's just constant reference to the technical data every time, every day.

What tools or software or hardware are you using most often?

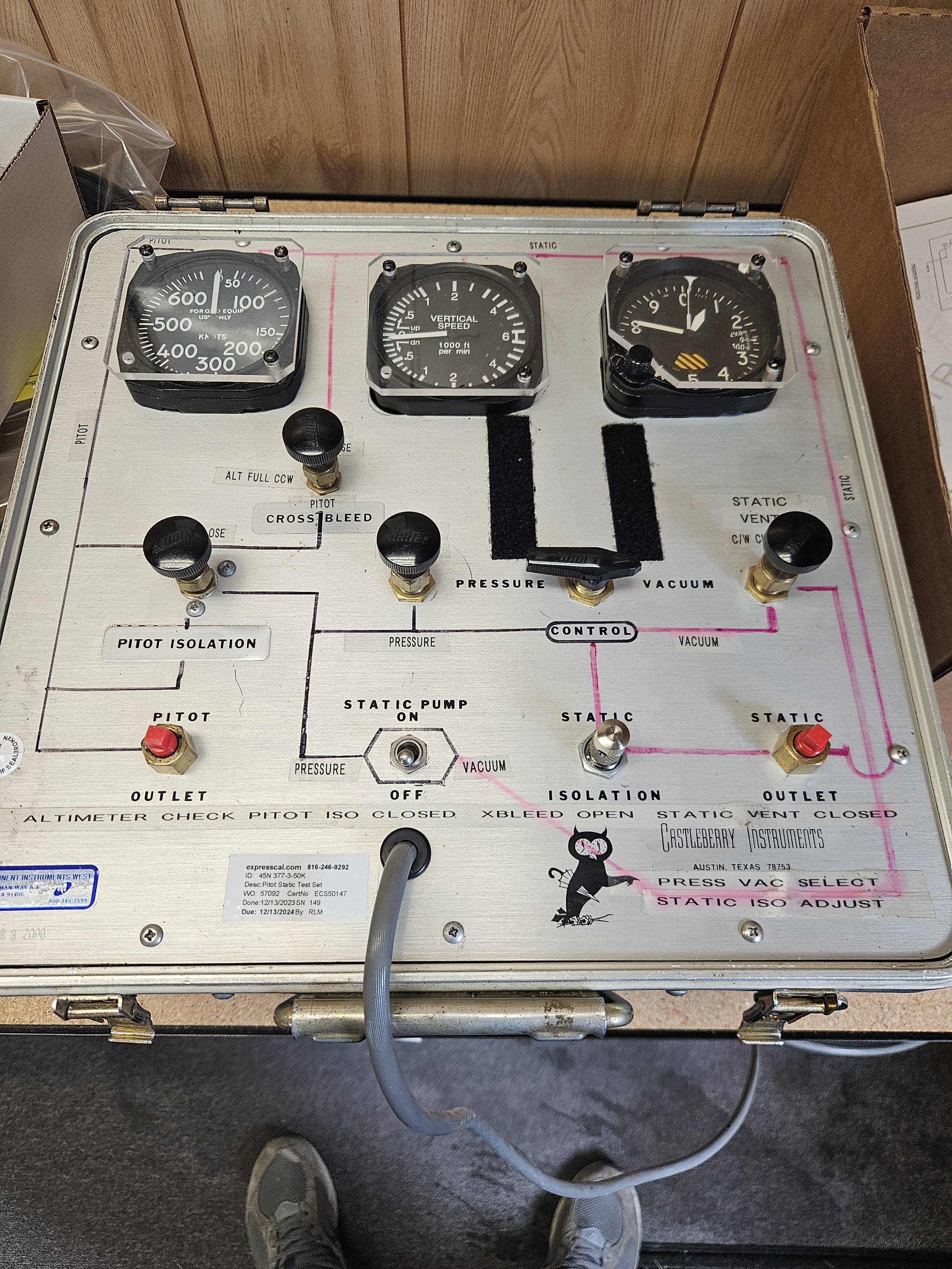

One of our big things we offer is what's called an IFR [Instrument Flight Rules] cert, and that is certifying the aircraft to fly through inclement weather. So on a nice sunny day, you're flying [what’s called] VFR [Visual Flight Rules], you can look out the windows of the plane and see where you're going and what's going on. In Instrument Flight [IFR], you're basically relying on the instruments in the aircraft to guide you to where you need to go. For that, I have a couple different test boxes that I can attach to the plane and use them to determine if the plane is IFR capable. And if it passes all my tests, then I can issue it an IFR certification, which is good for two years or 24 calendar months.

My test box hooks up to the pitot and static system of the aircraft. Pitot would be air pressure. As you're flying through the air, it measures how much air is coming into the lines and basically determines how fast you're going. The static air system is how high up you're going. As you get higher into the atmosphere, the air pressure gets lower. It's like a vacuum, right? You get less and less air up there. So what my test box does is simulate either airspeed or static air as we are going up into the atmosphere. Most of what I do gets certified to 20,000 feet. I can simulate the airplane going up to 20,000ft and back down and I measure what the box says versus what the instruments say in the aircraft. As long as it's all within tolerance, which is set by the government, then I can certify it.

Old test box for Pitot and Static systems | Photo courtesy John Hogan

With that comes the transponder. The transponder in the aircraft is what the plane is essentially saying to ground towers and other aircrafts where it is in the sky. My test box will interrogate the transponder and wait for a reply. If it's replying and it's all within the tolerance (again) set by the government, then I get to pass it. So [if] both those things pass, then it is good to fly IFR. Those [tools] need to be calibrated every year and they get sent out to a company somewhere to put them through the test so that I can then accurately test the aircraft.

How long does it take to do that whole process for one plane?

It depends, but I usually block off three to four hours for it. If it's just flying VFR, it takes five minutes for me to hook up and test the transponder because it's just me pushing a button. If IFR, it's a little more involved because I need to dig into the static system, which is basically a hose that runs through the aircraft. When I hook up my test box and I start running it up, say 2,000 feet, 3,000 feet, if it starts to leak, that means that there's a leak somewhere in the static lines. I need to trace through the static lines and check all the connections, the ports, and the instruments themselves to make sure that one of those leaks can be fixed. If they can't be fixed, that means it's probably an instrument that is failing, in which case we need to send the instrument out and have it exchanged or fixed. That can really start to take some time, depending on the aircraft and how many altimeters [the instrument in the aircraft that measures your altitude, how high up in the sky you are], because some have multiple, and then there's also multiple transponder systems. When you start getting into bigger planes, it takes time. But for the most part, the smaller planes that I work on, I'd say three to four hours to get all that done.

What are the typical career options in this field?

I learned a little bit about this when I was at that convention, and I also learned about this from my old supervisor and mentor here. He was in the military, and ended up going into avionics because he had a level of aptitude for it. You can get your A&P license, which is an Airframe and Powerplant [license] for general airplane maintenance. [It’s] more of a mechanic for the airplane that deals with the engine and the tires and the outside of the airplane. A lot of people who are in A&P school will also opt for learning more about avionics [rather] than becoming an avionics technician.

What you can do with it, though, your career choices would be – you could go commercial and be an avionics tech for, say, Delta or whoever at some big shop somewhere. You could go bench level, which is individual instrument repair. So when I say that we have a bad altimeter that needs to get sent out for repair, it goes somewhere to somebody, they take apart the instrument and repair it down to, like, a circuit board level. If we have a problem with a transponder, it gets sent out and they open up the box itself, look at the circuit board, try to repair it internally.

What I do is more installation and troubleshooting. I take these boxes that are already known to be good from the manufacturer, from whoever fixed it, and I install it into the plane. So most [of] what I do is the wiring and configuration of the systems. I don't make the systems, I don't fix the systems. I help design and install them.

Sorting old wire harness | Photo courtesy John Hogan

Outside of that, you could go more towards certifications. I know a lot of people who start up their [own] avionics business, and it's mostly just traveling certification. So he has a test box that he takes with him and travels to wherever somebody needs him to certify their plane. We used to offer that, but it takes a lot to travel around. It's more of a niche thing. If that's what you're good at and that's what you want to do, then by all means, go for it. We stick with the installation and troubleshooting.

What skills do you think are most needed for success in this field?

I would say a general electrical aptitude is necessary. We work hand in hand with a lot of mechanics and you try to talk to some of them about it, and some people are interested and have a general understanding. Some people just don't. It's just, “I don't understand how that talks to that. And I don't get why that information gets traveled on that wire, but this doesn't.” A general understanding of how electricity works as well is good. What else…? Well, just a call back to all the manuals. Being able to read and understand wiring diagrams is very important. That's where you get the bulk of your information for how to connect the systems together. And if you have a hard time reading those, it's going to make your job tough, I bet.

What is your favorite and least favorite part of this job?

My favorite part is getting to take a plane [with] old equipment and make it as up to date as the customer will allow. We had a really good job a few months ago where we had a guy's plane, and it was essentially straight out of 1970. He wanted us to do everything we could to make it as brand new as possible. That is a really fun job because we get to take the entire panel apart, take it all out, take the panel itself out, redesign a whole new panel. We have what's called Panel Pro. It's basically a CNC machine [a Computer Numerical Control machine, which can cut materials in 3D] that cuts a new panel. We have it powder-coated. We get them all the newest equipment. We wire it all up from start to finish, put in a whole new panel for the guy. But it takes a level of trust from the customer and it also is not cheap. It really takes somebody who's wanting this to be done on a plane and really investing some time and money into making this thing as cool as it can be.

Configuring an avionics system | Photo courtesy John Hogan

My least favorite part is everybody who comes in with an intermittent problem, meaning it comes and goes. Intermittent problems are the toughest to troubleshoot because they'll call me up and say, “Hey, this message popped up on my screen. I don't know what's going on or how to fix it.” And I say, “Okay, bring it in. We'll take a look.” He flies it in, and he says, “Oh, it disappeared. It's no longer a problem anymore.” Like, okay, great. So I have no way to replicate the problem, but it exists somewhere in there. That means opening up the panel, going into the wire harness, the connectors, the settings and the configs, and reading a whole bunch of manuals and trying to figure out what could possibly cause that message. The answer is usually three or four different things, so then you have to trace down each of those to see if there's an underlying cause. It takes a lot of time. Nobody likes it. Customers certainly don't like paying for all that time. Then when you do find the problem, it's, “Oh yeah, here you go. It's all fixed now.” And they're like, “Well, why do I have to pay for all the other stuff?” Still a lot of time [we] put into it, you know?

It sounds like a scavenger hunt.

It really is. When the messages that you get on the screens don't give you a ton of information, [it’s] like your check engine light on your car. What does that mean? It could mean a number of different things, and you have to take it into the dealership or somebody who's got a code reader to understand what that problem is. Even then, it just narrows it down a little bit. It doesn't tell you exactly what's wrong. It's a lot of time, a lot of energy, and not a lot of satisfaction in the end.

Okay, but what do you do? Please answer as if you’re explaining to your ten-year-old self.

I make sure that planes are able to do all the things that they can. I make sure that all of the instruments in the plane work properly so that the pilot can do [their] job better.