Product Manager

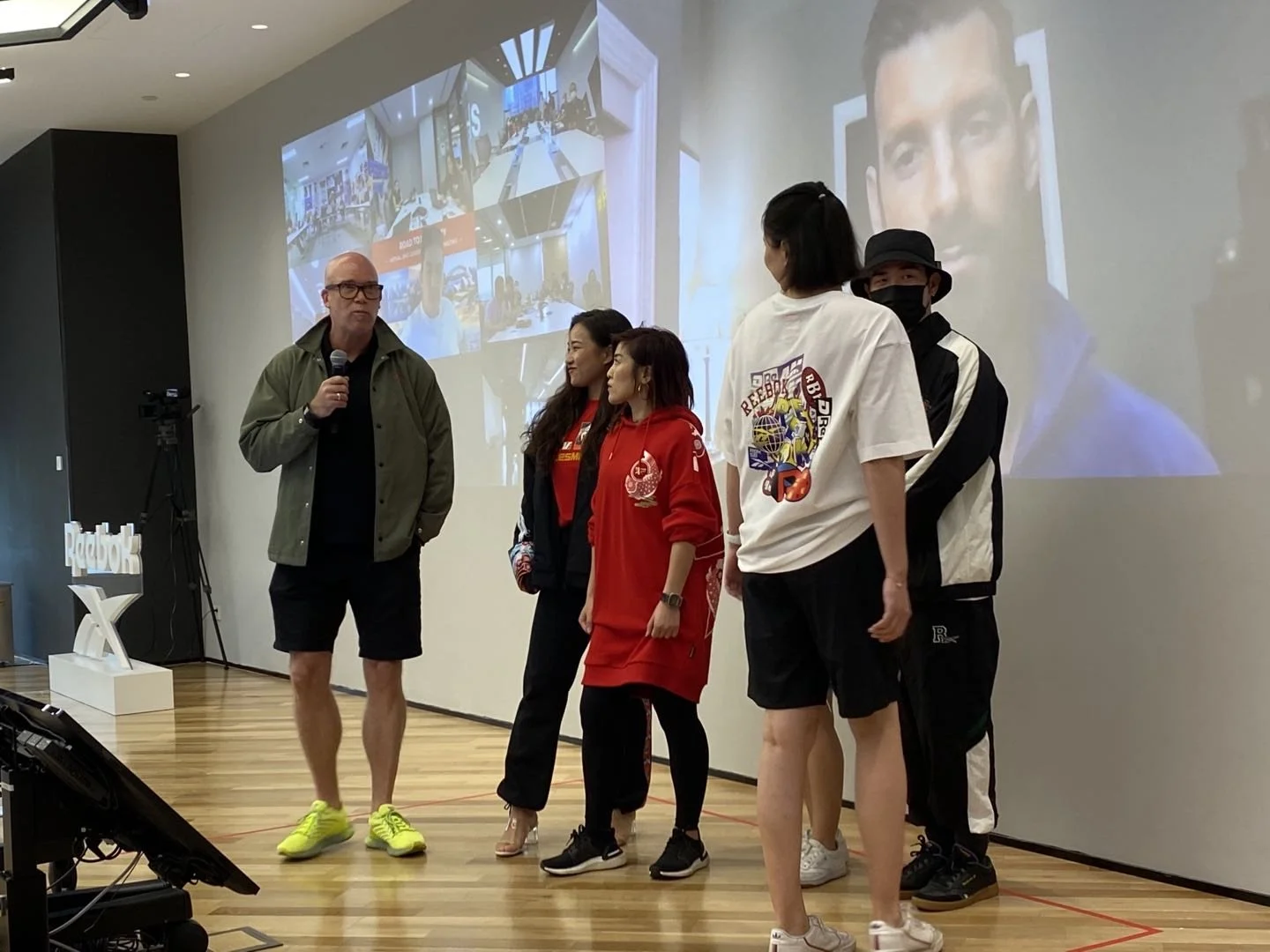

Photo courtesy of Eric Lonsway

“Product Manager” is one of those jobs with a hard-to-pin-down description. You kind of know what it means, but you couldn’t explain it to someone else. Lucky for us, Eric Lonsway, a veteran of the job, can. He fills us in to how he got there, what he did in the position, and what came after.

Name: Eric Lonsway

Occupation: Product Manager/Senior Director of Product Creation

Okay, But What Do You Do?: [I’m] part of a creation team that makes things, that solves problems for people, and then my particular role was planning which things were going to go to market, which we were going to try and sell to people, and then telling the story about those.

What is or was your official job title?

My last job title was, for years really, Senior Director of whatever category or product type I was working on. And my first and last job at Reebok, when I was in China, I was the Senior Director of Product Creation for all of Asia Pacific.

Could you walk me through your career to date?

Yes. And this is where I'll try and be concise, but not leave out the details that matter. I went to UCLA, and I needed to pay for school on my own, so I got a job in retail. It just happened to be for Nike. In my mind, it was just gonna be to pay for school. I knew Nike because I had been a runner and I used to study who made the best running shoes, hoping desperately it would make me better. It never did. But, you know, it was still fun.

It led to this career, because, once I graduated and had done an internship in what I thought I wanted to do–international finance–I realized those were not my people. So I stayed with Nike. I had been writing up reports on what consumers were buying when I was managing the store up in Eugene, Oregon. Somebody [saw] my report and said, “Hey, we'd like to interview [you] for this job as an assistant product manager.” And that's where it started. I got in there. Absolutely loved it.

Did that for Nike for nine years the first time. Once I moved up to Oregon, I started snowboarding because I grew up [in Los Angeles] skateboarding and being at the beach. The only reason that's important is because I got the snowboard bug and then I saw that Burton Snowboards had an opening for a job. I had about half of what they were looking for, but I applied anyway, and I ended up getting the job and moving to Vermont.

Burton was great because it was a small company–privately-held–and I was hired to be the Boot Product Line Manager. I ended up having to design boots, develop the boots, source the factories, do the quality control, look at everything, which was amazing, like owning my own business but [it was] Jake Burton's company, so he was paying for it. I met my wife out there. We had our first child out there. And then I got a call from Nike saying, “Hey, we're thinking about getting into snowboarding. Would you like to come back?”

At that point, the one bad thing about Burton was [that] Jake was there every day, which is great, but he expected everybody to be there when he was there: his hours were from 9:00 a.m until about 9:00 p.m. Every night. It was a great experience because I learned so much but [I thought] “Okay, this is a lot. I'm leaving before [my children] get up. I'm getting home, and they're already in bed.” That was not something I was a fan of.

Nike wanted someone with experience. So, we moved back. I was with Nike for another 21 years. I stayed in snowboarding for a few years. That ended up being absorbed by ACG [All Conditions Gear], which is the outdoor group. So I started working on hiking boots. Created a thing that started with Aqua Sock [and turned] into something else called Coastal Approach that was successful. And then I got offered a position in Amsterdam to be the FPM, the Footwear Product Manager. Amazing experience. You know, I grew up with a single mom in southern California. She was a bank teller. I [thought], “This is where I'm going to live and die.”

One of the things that's so amazing is you will have opportunities in your life that will take you places you never thought were possible. And that's what Nike was for me. So I did that for years, came back, got back into product management, became a Product Director later on, then got thrown into a new category they were starting called Solar. They were gonna take all the sandals and all the different categories they were creating and put it all together because it made sense from an efficiency and knowledge standpoint. And in my role I had development, design, and product management reporting to me.

And then I went to the executive committee to say, “Hey, can we bring ACG back?” We got permission, and so I did that for probably six years. My last job at Nike, I was Head of Skateboard Footwear, which was fantastic for me. I wanted to get to China because I saw a lot of things happening over there [but there wasn’t anything] with Nike. So, in 2017 I retired and was going to start a business with my son but then I got a call, about a year and a half after retiring, from Reebok saying, “Would you like to come to China and open our creation center for us for Asia Pacific?”

I had done footwear, I had done accessories. I'd even done hard goods before, but I'd never been in apparel creation. So it was an opportunity to do all of those and lead and actually hire the team and set everything up. We were empty nesters at that point, so we decided to do it. We moved to China and quickly became a very big part of the country's businesses, which was amazing. And then Adidas, who owned Reebok at the time, decided to sell Reebok and shut it all down. Adidas absorbed most people because we were doing good things. I got an extension for another couple years, became the Senior Director for Neo, which was a teenage-aimed line for apparel and footwear–just in China. We lived through Covid over there, and couldn't get out of China, it was too difficult to get back in. We hadn't seen our kids for a while so when it was time for the contract to be re-upped, I said, “No, thank you.” And now I’m back here, doing what I love, which is working retail.

Can you talk a little bit about training? What helped you grow with the job?

There wasn't any formal training. In terms of the product management side, I think retail was probably the best training of all because you get used to working with people. In retail nobody cares. [Customers] will go, “I don't like that product.” They tell you the truth. Having to deal with people, work through [their disappointment] and get them –if not completely turned around and happy again–at least to a point where they're not angry anymore [is part of the job].

Product management is about communication. You have to be a good collaborator, you have to be a good communicator, because if you're not on the same page and you don't have your team on the same page, then the product is probably not going to be right and it's probably not going to make it. So it's a lot of wasted time, work and energy for a lot of people. The other thing is, I think, observation skills, critical analysis, and thinking because at the end of the day, it is a business. You're trying to solve problems for people, but if you don't know what the problems are, then how are you gonna solve problems?

The reality of it is things change and you're either going to keep [making] the same thing and fail eventually because nobody wants it anymore, or you're going to keep moving along, knowing what's happening. And if you're really good, you can actually be on the front end of it and give [customers] things they didn't know they wanted until you brought it to them.

What are the pros and cons of working in a company for a long time?

I think, first, [do] you like working for the company? Because otherwise you're probably not gonna be there if you don't like what you're doing. I was very lucky. All the categories I was able to work in were of interest to me. I think the thing that was great about working long term [with Nike] was that you really start to see how the company works and how to get things done.

You become a little bit more of a community, a little bit more of a team in a longer term relationship. Now there's good and bad with any long term relationships. And part of the bad, in this case, was I saw things change at the top level of leadership, but it made its way down. When politics became more important than performance, it was time [to go].. It was a natural thing for me in the end. I think when you're younger and newer to a company, you're also willing to put up with a lot more [stuff].

Photo courtesy of Eric Lonsway

Can you explain who you were managing when you were product manager, who was on your team, what kinds of roles made up the team?

So, that's an interesting thing. Let me take a step back. The product creation team is a triad of people: product management, design, and development. And really none is more important than the other. I was responsible for managing the product line. But was I responsible for the developer or the designer? No. However, I was responsible to make sure they had everything they needed, especially from me. I always used to illustrate it, when new people [joined] the team, like the old milking stools that were three legs. If one of them is longer, the stool tips over. If one of the legs is missing, the stool tips over. It only works if they're all in balance.

At the end of the day, the rules are that the designer is kind of the creative problem solver–everyone’s a problem solver, honestly. Developers take that 2D object hen go, “Okay, so can we actually do that design the way it's designed?” And the product manager is the communication conduit in and out of the triad. For instance, it was my job to make sure that feedback was heard, like, “We really do have to hit this price if we're going to get this out there.” And then I would also communicate back out to merchandising, sales or leadership what we were doing, why, who the consumer was, what the story was… It was my job to make sure that everything was smooth.

Were the teams you were involved in actually three people?

It depends on the size of the category and the size of the product line. In snowboarding, yeah. I had one designer, one developer, and that was real easy. In bigger categories, like when I was at ACG outdoor, they would try and spread out the whole product line amongst designers so they wouldn't get too buried with one thing or another. [Same with] developers. And there were other product managers also vying for the time of the same designers and developers..

What's the career trajectory for a product manager?

My path is definitely one of the paths you can take. You'll go from being a Product Manager to a Senior. You're still doing work, you're still in the weeds. The hardest transition is if you go to the next level, which is a Director. Now you're not responsible for the product line minutia anymore, you're responsible for the entire line and how your team is doing with that line. That seems to be the hardest one for folks because you go from being a very good doer to now someone who is mentoring, coaching, teaching (if you're doing it right).

If you do learn to be a mentor, a teacher, a coach, you can go up to senior director roles. I have friends who've gone all the way up to CEO. I've had friends who've gone into sales from product management. I've had people go into merchandising from product management. You could go into brand marketing as well. There's a ton of different places to go.

It's a career that trains you for a lot of different things. You have a lot of room for exploration after.

Yes. There's a lot of [jobs] that can transition into anything. When I went to college, probably 90% of people thought “I'm just gonna be a doctor or a lawyer.” I was going to be a doctor. I went in pre-med. I ended up majoring in economics, and I explored a lot of things. I took music classes. I took science classes. I worked with cadavers. If you're open and you want to explore things, almost anything can take you anywhere. You just gotta figure out where you want to go. And even then, if you think you want to go one way and you get there and there's a dead end, you can go another way. Almost no career path is a straight line.

Something that I found very impressive when I was lurking on your LinkedIn were all the different sales goals that you hit and then exceeded. Can you talk a little bit about how you reliably did that?

Well, first, thanks for noticing. To me it came out of really noticing consumers and what they wanted. I always tried to keep the teams very focused on solving those problems and doing it for a good value and having a story. If you have a story behind the product and you solve the problem for them, even if it's expensive in terms of an actual cost, but the value is there for people, then it's not expensive. I tried to do that as much as possible and I became known as a little bit of a fixer. Knowing your consumer and who you're going after is crucial. And if your team knows that as well, then everybody will make the right decisions. Not that you're not going to fail sometimes, but that's okay. Learn from it, right?

What did you do to stay in touch with the customer and make sure you were thinking the way someone buying this product would?

I always made sure that we as a team got out, observing consumers in their natural habitat, if you will. My favorite thing is to go grab a coffee someplace where there's a lot of people and watch what they're doing. In the case where it’s performance [shoes],go to places where people are doing those things, right. Just start shooting the shit with people. Go, “Hey, what do you really like about that?” People will talk about things they love. Be willing to go do that and be willing to really hear what they're saying, because there's listening and there's hearing.

And just like there’s seeing, there's observing. Being able to discern what's an opportunity versus something that's not is a big part of it. And diversity of thought. Everybody thinks a little differently from their experiences and such. You can observe anything, your coffee mug there, take that away and bring [people] in one at a time after they've all seen it together and they're going to describe it differently. But when you take all their descriptions, you're going to get a very accurate description. It's the same thing with solving problems.

That's how you do it. Go out. Don't sit in the building. Don't look at websites because you're getting somebody else's curation of their thoughts. It might be what's “happening,” but also might not be the right thing for your brand or your category or whatever you're working on.

Photo courtesy of Eric Lonsway

Which brings me to making mistakes. What would you say are mistakes that you've seen happen a lot and how do you fix them?

First of all, mistakes are going to happen, and it's okay. If you're not taking risks, making mistakes by trying to do the right thing, then how are you learning anything new, right? Now if you're making the same mistake over and over, someone's gonna have a different conversation with you. It's okay to make mistakes. That's number one. Second, and I kind of talked about it earlier, thinking you're more important than anybody else on your team [is a mistake]. But the biggest mistake I see in product creation is when either someone on the team thinks [the product is] for them so they don't want to change no matter what. You have to let people talk to you. It's not about you. It's about who you're solving for.

Advice that I think probably works for more than one career.

Absolutely. Last thing, too, is when you do have a good idea and you've done all this research, if you're in a company at some point, [you’ll get] feedback. Somebody's going to go, “I don't like that.” You have to learn not to be defensive because again, it's not personal. It's business. It’s a tough thing to learn. But it's an important thing to learn.

Favorite and least favorite part of your job.

Oh, that's easy: favorite, anyway. The coolest thing ever doing product creation, is if you just happen to be out somewhere and someone's talking about a product you helped work on, and they're talking about how good it is and how it did this or it did that for them. Then you go back and tell everybody “I just heard this!” Sometimes you just happen to be in a store buying something for yourself, even, and you'll hear it. You're working [on something for] 12 to 24 months. Innovation could be longer, it could be 3-5 years. So when it finally gets there, and you're working on something that, [let’s say], performance and you see an athlete really perform well in it, that’s awesome.

Least favorite is when you've done all the research, and maybe because you didn't tell the right story or it's a little bit ahead and some people haven't seen it yet, a product either doesn't get supported or doesn't even ever make the market. Or when you do come out with something and it connects, but connects in a very small way at first because it's brand new–not having the patience as a company to give it the time to grow. At one point, I actually bet my job on something. The guy that was in charge of making sure the product got to market said, “Would you bet your job on it?” I said “Yes.” Stand behind it, my team worked hard on it.

What's something you didn't expect you’d have to do in this career?

I think, especially in product management, there's a lot of ambiguity. There’s not a clear career path. [In other careers], when you get in, you go, “Okay, I'm gonna start here. But I know, in this amount of time, if I've done these types of projects and these kinds of critical experiences, I'll at least be eligible for the next role that comes up in that zone.” In product management, it's very different because there's nothing tangible other than the numbers. It's like being rowed out to the middle of the lake and dumped off. And while you're swimming to shore, they light the lake on fire and they're shooting at you. If you make it, check. But just know you're gonna have to duck, you're gonna have to go to the side. You're gonna have to do different things. You're gonna have to be agile, be good with change.

But really, because it's so ambiguous, you have to know where you want to go and know it may not be a straight path. Talk to people who've gotten to where you want to go and ask them questions like, “What are some of the things you did that you think helped you?”

What would you say are some skills that have helped you?

Let's see. I think in addition to all the stuff I talked about before, communication, critical analysis, being good with ambiguity and change are incredibly important because, especially in private [sectors]–don't wait for someone to tell you what to do. If you know where to go, just go. Ask for forgiveness later, don't ask for permission. And I always try to simplify as well. You'll see a lot of people make things way too complex for no reason, and sometimes it's to justify their position. A lot of people who don't really know what they're doing go, “We'll make things really complex so that people are like, ‘Oh, man, I could never do that.’” They add bureaucracy. They add a bunch of stuff that shouldn't be there. Always try and work with the ones you see making things simple. Everything is complex enough as it is. Make it as simple as you can.

You touched on this a little bit earlier, but how do you spend your days as a product manager?

You are in the office most of the time. That's the reality, because you're working on stuff and you've got teams. I think email is a great tool, but I'd rather go talk to somebody. I would normally get up from my desk, go find who I wanted to talk to, and if they were there with their headphones on, I knew they're cranking on something, like a designer. I'd leave them alone, but if they were sitting there kind of doing other things and they didn’t have headphones on, I'd go ask the question. If you're on an email, you might go back and forth 15 times before you actually get to the answer. If you go talk to them, in under five minutes you've got the answer, usually. And if not, the two of you go talk to whoever else you need to talk to get the resolution. I [also] used to try and get ahead of things. Your leader always asks for certain things, so as soon as you get it, go show them.

I had one Head of Product, and anytime we got new samples in, I would do a little walk by with the samples. If his office was open I’d show him and take him through everything. It was a great way to stay ahead and get him talking to other leaders about all the great things we were doing. It just buys you a little bit of goodwill no matter what. It's always good to have your boss excited about what you're doing versus wondering what you're doing. You're also showing them to get them to give you a first reaction sometimes. Like, “That's really cool, but what's that?” And if you get them on board, they'll also help when you do have those bigger meetings.

The other thing is going to the factories. Just like we talked about, emailing back and forth–or in the old days, faxing–isn’t the quickest, easiest way to get things done. When you go to the factory with your triad that you're working on the product with, you can save millions of dollars. It's important to get over there. They're experts on creation, so they can talk you through stuff. It's really fun and educational.

It sounds pretty varied, you're not always tied to your desk, writing emails.

Oh, God, no, no.